-40%

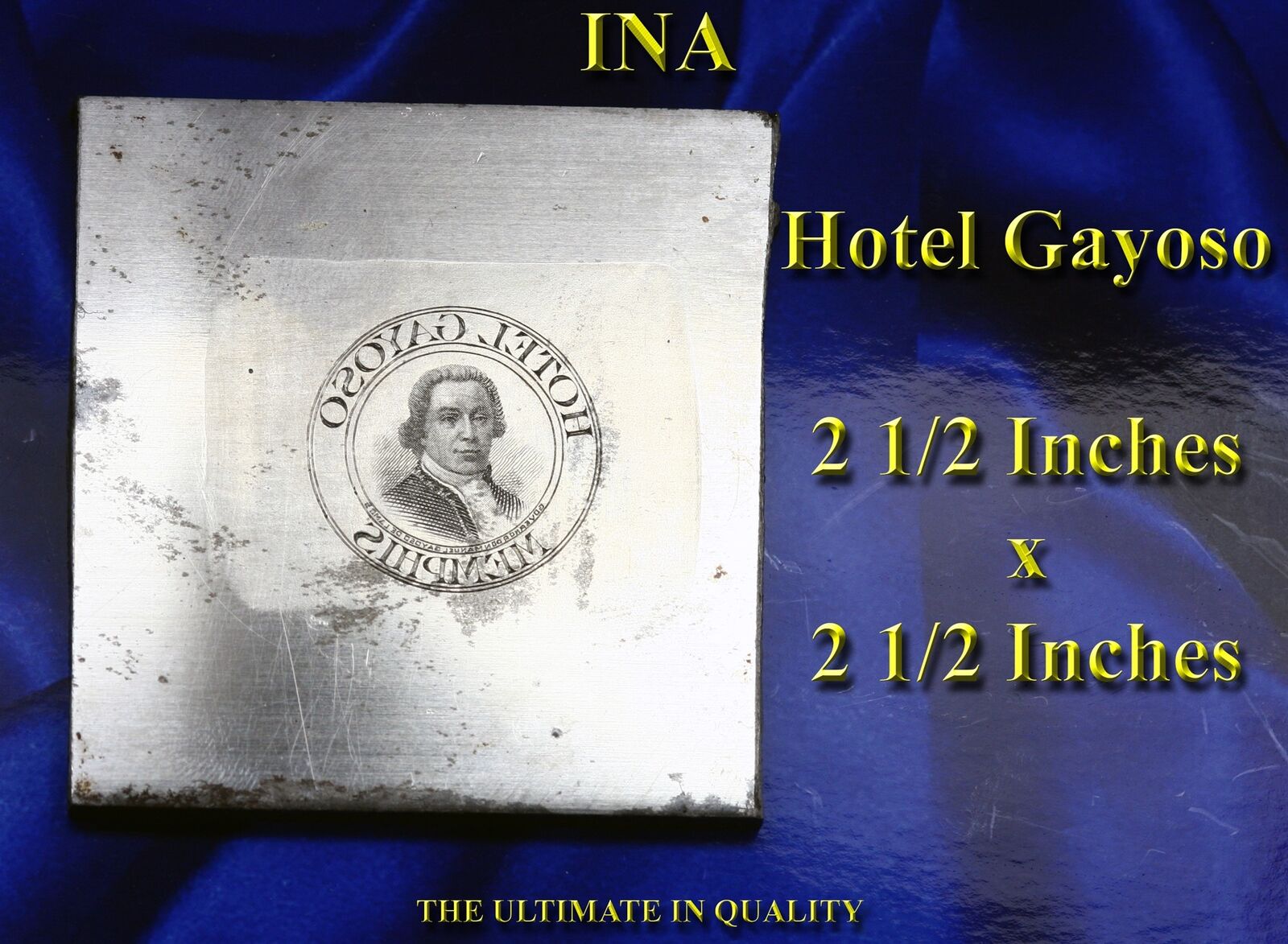

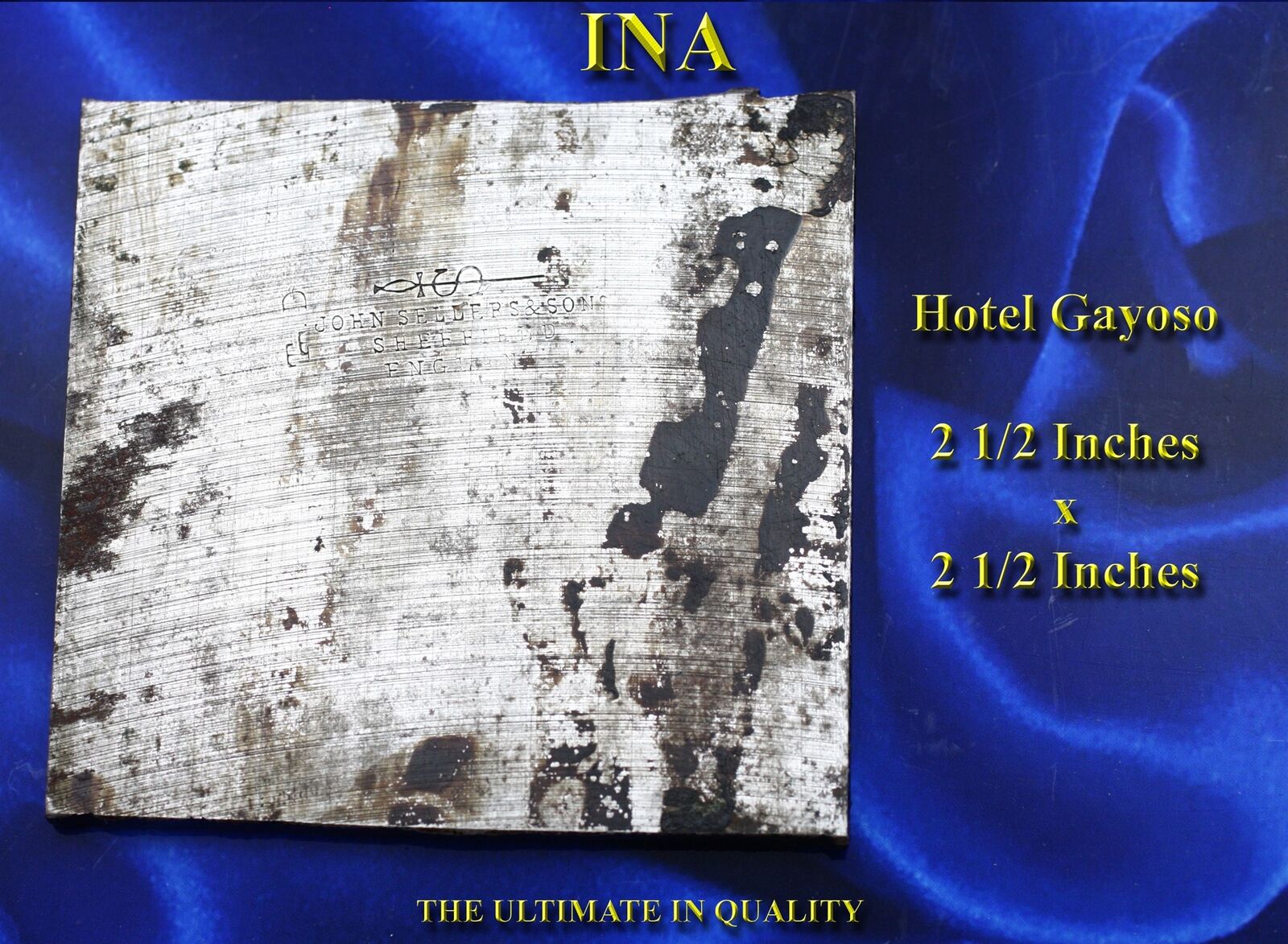

INA Hotel Gayoso Memphis Tennessee Steel Engraved Plate of the hotel seal Rare

$ 208.56

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

AuctionsBuy It Now

Ending Today

View Feedback

Store Newletter

Visit Store

Contact Me

A vision of grandeur for the developing river metropolis at Memphis, the Gayoso House was built by Robertson Topp, a wealthy young planter. Topp was involved in the development of South Memphis, an area of houses, commercial buildings, and a hotel designed to grace the young city with high architectural style. He commissioned James Dakin, a founder of the American Institute of Architects, to design the structure, which was constructed in 1842. Its Greek Revival portico was easily recognizable from the river. In the late 1850s Topp continued his efforts to bring architectural distinction to Memphis, when the Cincinnati firm of Isaiah Rogers, designer of the Tremont House in Boston, contributed to an addition that almost doubled the Gayoso's original 150 rooms. The addition featured wrought-iron balconies overlooking the Mississippi; the supervising architect was James B. Cook, an Englishman who stayed in Memphis for the rest of his architectural career.

The Gayoso House became a Memphis landmark, an oasis of modern luxury frequented by travelers passing through the city by river, road, or rail. With its own waterworks, gasworks, bakeries, wine cellar, and sewer system, the hotel offered amenities far beyond those available to the rest of Memphis. The indoor plumbing included marble tubs and silver faucets as well as flush toilets.

The Gayoso House burned on July 4, 1899. To replace it, James B. Cook designed a new hotel. His U-shaped construction surrounded a courtyard screened from Front Street by a row of columns, which are no longer extant. Goldsmith's department store bought the hotel in 1948 and used it for offices and storage. Fifty years later, however, it was restored for use as downtown apartments, residences, restaurants, and offices.

Item#: 9580

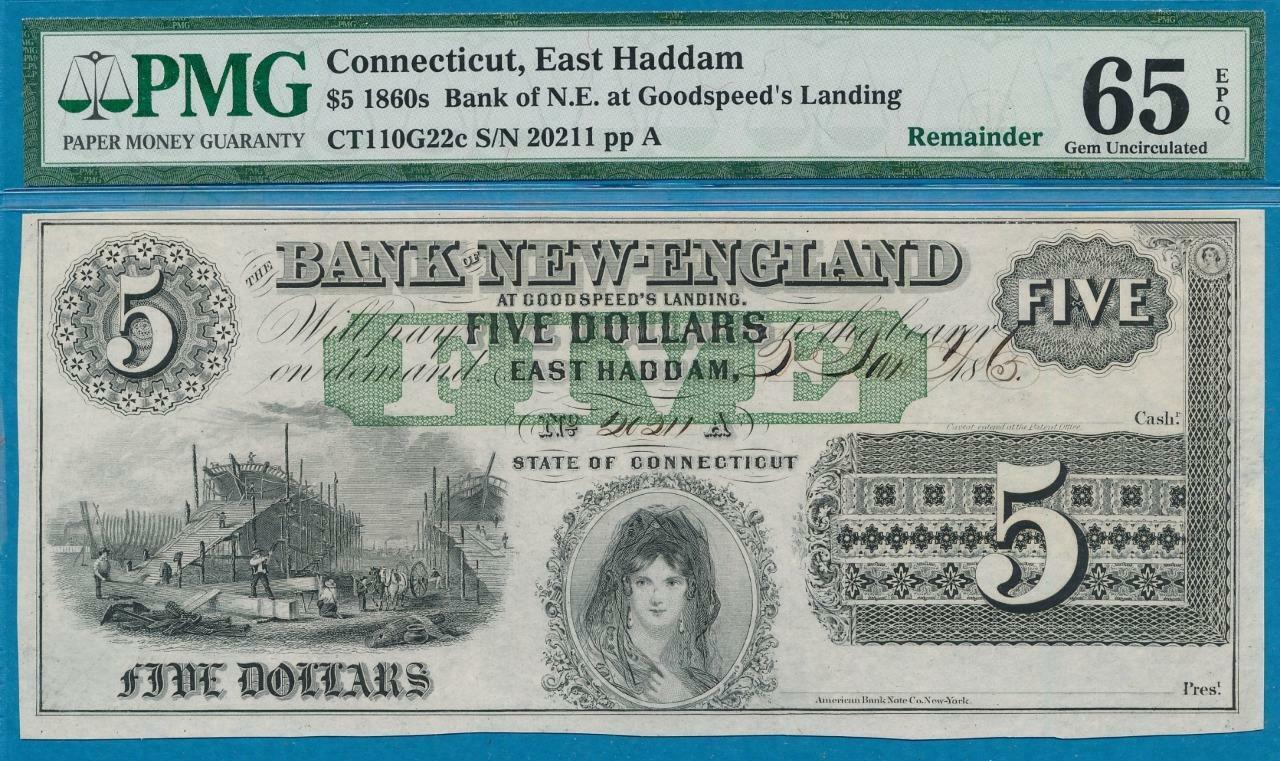

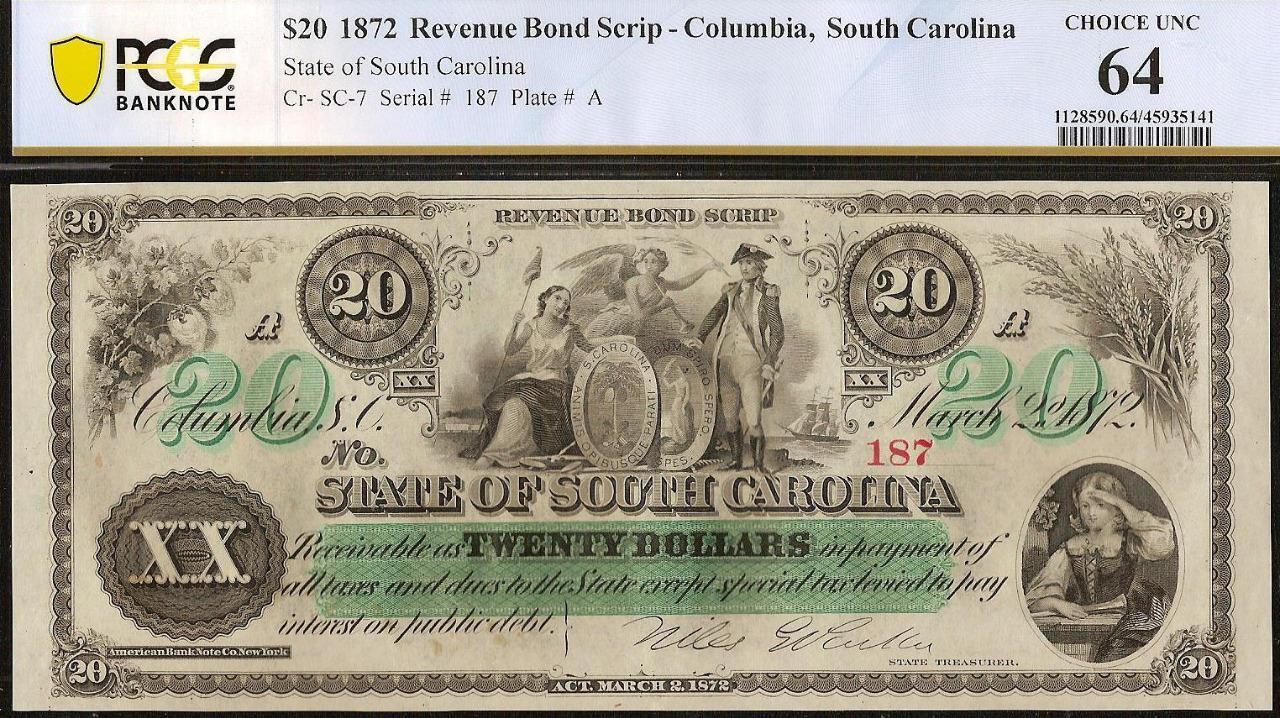

A note on quality of Obsolete Bank Notes.

Unlike regular US Government notes, bank notes were not printed on the finest of cotton-bond paper or with the best of inks. They were not meant to circulate for a long period of time or circulate throughout the nation. They usually circulated on a local or state level, and probably not more then a few years at best. They were printed on whatever paper was available at the time. On some notes one can see some of the wood or pulp chips in the paper. In some cases, they were printed on earlier notes that were no longer in use. The technology of acid-free paper was not there yet, as seen with some of our national historical documents, and paper was much scarcer than we can today imagine.

These notes had to be printed on semi-wet or moist paper, or the ink would not properly adhere. They were very labor intensive, and were printed by hand, one side at a time. They would manually ink the press, place the damp sheet in it, and run the roller over it. The sheet would be hung to dry, and the same process of wetting and printing would be repeated for the reverse. In the case where more than one color was used, the process would have to be repeated for each color. Unpurified water was used in the wetting process, thereby introducing more minerals or impurities to the paper. As a consequence, many of these notes are very difficult to locate without discoloration, color bleeding or what looks like water staining, due to the wetting process. As if that was not enough, they were individually cut with scissors or crude cutting boards, making them very difficult to find with good margins, or the design itself not cut into it.

When grading them today, the coloration, bleeding or some stains, do not deduct from the grade, for the great majority have these problems. Margins, alignment and condition of the paper itself are the main grading points. However, when finding some of these notes without many of the usual problems, one should recognize that it is not the norm. That is one of the reasons why I have virtually all of these notes certified. They get sealed in archival holders, minimizing the aging and toning effects by not being exposed to the elements, and it also gives the client reassurance as to its authenticity and grade.

Warning:

I have seen some very white and super clean examples, but, upon close examination, they were nothing more than modern reproductions.

Powered by SixBit's eCommerce Solution